Gábor Halász

Education Policy Reform in the

European Union

(Education policy for growth, employment and

social cohesion)

Manuscript of the published version. To be quoted as follows:

Halász, Gábor (2013). European Union: The Strive

for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth in: Yan Wang (ed.): Education

Policy Reform Trends in G20 Members. Springer. pp.

267-288

Content

Education sector reform policies of

the EU

Policy reforms and strategic goals

in the education sector

Policies related with particular subsystems

Lifelong learning as a general policy

framework

The content of community LLL policy

A central element: reforming

qualification systems

The higher education modernisation

agenda of the community

The implementation of community education

policies

Governance and policy instruments

The future of education reform policies

of the EU

Abstract

This article aims at presenting the key

features of the education policy of the EU as part of its overall reform

agenda. It exposes the specific strategic community priorities related with the

various subsystems of education (vocational training, higher education, school

education and adult learning), and also the horizontal goals that overarch the

subsystems. The main components of the lifelong learning paradigm, as a general

policy framework, are presented, with a special focus on the EU’s higher

education modernisation agenda. A detailed picture of various policy

instruments the community uses to support policy implementation is also

presented. The final section of the article analyses the possible future developments

of education reform policy in the EU.

---

Policy reform in the case of the European Union

has a different meaning than for all the other G20 members. The EU, in contrast

with the other G20 countries, is not a state. Although it shares many features

with “normal” nation states, it is a unique political construct that cannot be

described as a “real state”. Even though it has its citizens, its parliament,

its government and its policies, and it does operate specific mechanisms of

governance these are different from those characterising “real states”. The EU

is more than an intergovernmental

international organisation (for example, in certain policy areas it has

full regulatory power) but less than a federal

state (like the United States, Canada or Germany) because its constituents

are not “provinces” with limited jurisdictions but powerful sovereign nations.

This unique political construct has, however, highly elaborated policies even

in those sectors where its regulatory power is missing or is very limited –

such as education, for example – and it has a highly developed repertoire of

implementation instruments that are put into operation even in these sectors.

It can and, in fact, it does initiate policy reforms and it does have the

capacity to implement them.

The aim of this

article is to present the key features of the current education policy of the

EU as part of its overall reform agenda. The article intends to show that the

EU has been pursuing marked reform and modernisation policies in the education

sector which are strongly embedded into and determined by its overall policy of

social and economic modernisation. A special focus is given to the question of

how reform policies, which had been defined at community level, are implemented

in the member states. This focus is justified by the fact that implementing

reform policies in the EU context is particularly challenging since the EU

consists of sovereign members states which have almost full control of

governing their education systems. The article does not have the intention to

present specific policy reforms within specific EU member countries: it deals

only with community level goals and actions.

Education

sector reform policies of the EU

In the field of education the EU has a

well-focussed reform policy which aims at enhancing modernisation processes in

its member states. This reform policy is directly connected with its broader

policy for “smart, sustainable and inclusive

growth” as formulated in the so called EU2020

strategy proposed by the European Commission[1] and adopted by the main

decision-making and law-making body of the Union: the Council of the ministers.[2] “Smart” refers to the goal of founding growth on the most advanced

technologies, “sustainable” refers to

both environment friendly and efficient growth and “inclusive” refers to the goal of enhancing the maintenance of

social cohesion.

The direct antecedent of the EU2020 strategy is

the so called Lisbon strategy,

adopted by heads of states of the European Union one decade earlier, in March

2000. The latter set goals for social and economic development to be reached by

the end of the last decade. The EU2020 strategy is, in fact, the continuation

or the prolongation of the Lisbon Strategy in an enriched and updated form.

They both have been urging major reforms in the “European economic and social

model” in order to improve the competitiveness of Europe while reinforcing

social cohesion and protecting the environment. They both have been translated

into specific sectoral strategies, including one for the education sector.

During the last decade this was the “Education and Training 2010” strategy, and

its prolongation, currently in force, is called “Education and Training 2020”.

Policy reforms

and strategic goals in the education sector

The current “Education and Training 2020”

strategy, proposed by the European Commission, was adopted by the ministers of

education in 2009,[3] that is, prior to the overall “big”

growth strategy. This is an important fact because it shows that the education

sector is not simply implementing the “big” strategy but it also plays a kind

of forerunner role. The prominent role of the education sector in the Europe

2020 growth strategy is shown even better by the fact that from the 8

measurable key policy targets (“headline targets”) approved by the heads of

states in summer 2010[4] two are directly related with

education (early school leaving and tertiary graduation) and three others

(employment rate, R&D and poverty reduction) are strongly, although

indirectly linked with the performance of the education sector (see 1. Table)

1. Table

Europe 2020 targets[5]

|

Targets |

Estimated

starting value in 2010 |

Target value by

2020 |

|

1.Employment rate

(in %) |

73.70-74% |

75% |

|

2.R&D in % of

GDP |

2.65-2.72% |

3% |

|

3.CO2 emission

reduction targets2 |

-20% (compared

to 1990 levels) |

-20% (compared

to 1990 levels) |

|

4.Renewable energy |

20% |

20% |

|

5.Energy

efficiency – reduction of energy consumption in Mtoe |

206.9 Mtoe |

20% increase in energy

efficiency equalling 368 Mtoe |

|

6.Early school

leaving in % |

10.30-10.50% |

10% |

|

7.Tertiary

education in % |

37.50-38.0% |

40% |

|

8.Reduction of

population at risk of poverty or social exclusion in number of persons |

Cannot be calculated

because of differences in national methodologies |

20,000,000 |

According to the text adopted at the highest

political level the goal of the community is “improving

education levels, in particular by aiming to reduce school drop-out rates to

less than 10% and by increasing the share of 30-34 years old having completed

tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40%”.[6] This has sent a very clear message to the member countries: in the context

of the current financial crisis they should restore the balance of their

national budgets so that spending on education and training remains a priority.

The specific education sector strategy adopted

in 2009 defined four major objectives: (1) “making lifelong learning and

mobility a reality”, (2) “improving the quality and efficiency of education and

training”, (3) “promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship” and

(4) “enhancing creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship, at all

levels of education and training”. Three of these four objectives are not new:

they have been present in the sectoral strategy since the beginning of the

previous decade. The fourth one (creativity and entrepreneurship) has also been

supported by the community for a longer time, even if it did not figure among the

big sectoral objectives set in the previous main strategy document. Under each

of the four priority areas a number of specific key policy initiatives have

been launched.

The policy initiative that might have the

strongest and the deepest influence on the development of the education systems

in the member states is the reform of national qualifications systems

triggered by the adoption of the European Qualifications Framework (EQF).[7] This is a so-called “meta-framework”

which aims at orientating national qualifications reforms within the member

countries. The latter have committed themselves to establish their own national

qualifications frameworks following the EQF principles, that is, linking the

level of each national qualification to the European standards and describing

specific qualifications in terms of learning outcomes defined as knowledge,

skills and competences. The new national frameworks are to mediate towards the

national education systems a common way of thinking about learning and about

the formal recognition of outcomes of learning. Although this is a fully

voluntary process, based on the autonomous decisions of each member country, it

would be difficult for any of them to keep away from this harmonisation of

national qualifications systems. In fact, the progress of this process shows

that voluntary cooperation might often be a stronger unifying force than

compelling regulations.

This is also demonstrated by the much better

known Bologna process by which

European countries are creating a European Area of Higher Education which also means harmonising

higher education systems. It is important to stress that this is an

intergovernmental process, launched outside the European Union by countries among

which several have never been and will never be members of the EU. While

harmonising the structure of educational system of its member countries is

formally excluded by the EU Treaty, this is something that can be done and is

being done on a voluntary basis. The European Commission supports the Bologna

process by its implementation capacities but it is not the “master” of it. The

commission has its own higher education policy priorities that actually go

beyond the scope of the Bologna process as they include reform goals related

with funding and governance which are not part of the latter and

they stress particularly strongly the mission of higher education in enhancing economic

growth and competitiveness.

Policies

related with the particular subsystems of

education

Traditionally vocational training has been the strongest component of community

education and training policy because this was the only education-related field

in which the original Treaty of Rome has

endowed the Community with formal competences. This was extended to general

education only in more than three decades later with the Maastrich Treaty. Vocational training is still a central component of the

policies of the Union but today it is strongly embedded into a more general

policy of skills and human resource development. This policy area has always

been strongly connected with employment policy, and for more than one decade

with the policy of lifelong learning which became part of the employment

strategy of the Union developed after the conclusion of the Amsterdam Teaty

in 1997. A key element of vocational training policy has been the efforts to

make vocational qualifications mutually recognised and transparent in order to

enhance the free movement of labour. The Union has significantly contributed to

promoting the value and social recognition of vocational training in the member

states.

Since the eighties higher education has also become a key policy area. Originally the

related policies and measures were focusing on mobility, inter-university

cooperation and strengthening linkages between higher education and industry

but since the first part of the last decade the Union has been promoting a

general modernisation strategy that goes well beyond the original focus. Linked

with the Lisbon strategy, its departure point is a rather gloomy picture of the

state of higher education in Europe, or, as the Commission has put it

diplomatically in its most recent communication: “the potential of European higher education institutions to fulfil their

role in society and contribute to Europe's prosperity remains underexploited”

(European Commission, 2011a; 2). It has proposed reforms or improvements in

three specific areas: curricula, funding and governance. The curriculum reform

component aims at making teaching better connected to the needs of the world of

work and make European universities more attractive globally. Funding reform

aims at enlarging and diversifying the funding basis of higher education, and making

it less dependent on direct state funding. The aim of governance reform is to

make universities more autonomous, more accountable and more entrepreneurial.

School policy is a relatively recent component of community

education policies. The strongest element of this is the decision taken by the

Council and the European Parliament in 2006 to support the development of eight

key competences in the school systems

of the member countries. Based on a strong mandate, given by

the heads of states in Lisbon in 2000, and after years of difficult

professional debates and negotiations the Commission proposed eight key

competences that all European citizens should possess (see box).

Although the recommendation of the Council and the European Parliament is about

key competences “for lifelong learning”,

that is, formally they are not linked to any specific sub-systems of the

education system, and the legal text does not mention the word curriculum, it

is clear that this has a major impact on the conception of school education and

school curricula. This has been made clear when the commission launched, in

2008, a public debate on the question of “What should our schools be like in

the 21st century?” and the theme of key competences was in the centre of this

debate. The policy proposal of the Commission emerging from this debate was

entitled “Improving competences for the 21st Century: An Agenda for European

Cooperation on Schools” (European Commission, 2008), and it placed the

implementation of the key competence recommendation into the focus its proposed

school policy. The recommendation, although unevenly, has had a significant

impact on school policies in most member countries, often supporting ongoing

domestic reforms targeted at standards, teaching practices and assessment (Gordon et al., 2009).

The European Key Competences[8]

ð Communication in the mother tongue;

ð Communication in the mother tongue

ð Communication in foreign languages

ð Mathematical competence and basic competences in science and technology

ð Digital competence

ð Learning to learn

ð Social and civic competences

ð Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship

ð Cultural awareness and expression

Besides the definition of key

competences the professional development of teachers has become a cornerstone

of community school policy. In the second half of the last decade education

ministers meeting in the Council have adopted several decisions on this theme,[9] recognizing the

strategic role of the quality of the teacher labor force in educational

development. The theme of teachers was also the first among the thirteen action

areas defined on the basis of the Lisbon mandate in the “Education and Training

2010” program which guided the education policy related activities of the

community during the last decade.

A fourth area seen as a subsystem of education is adult learning. In 2007, after a

Europe-wide consultation process the Commission proposed a separate policy

package on adult learning which was backed, later on by the Council and the

Parliament.[10] This was a kind of

renewal of the recognition of “adult learning as a key component of lifelong

learning” which has already been well reflected in the fact that participation

in lifelong learning of adults is one of the major sectoral benchmarks in education.

According to this benchmark, set originally in 2003, by 2020 15% of adults aged

25-64 should participate in adult learning as measured by the European Labour

Force Survey which „asks about participation in formal and

non-formal learning in the 4 weeks prior to the survey” (European Commission, 2011b; 34).

Horizontal policies

There are several horizontal

EU policies and priorities in the education field that are not necessarily

linked with any particular subsystems of the education system although in some

cases they are connected stronger with one than with another area. Perhaps the

most important of them is supporting equity

which has been present in education-related community policies since the

beginning of cooperation in this sector in various forms, such as fighting

against school failure, facilitating transition from school to work, promoting

“second chance schools”, supporting the integration of children with special

needs and that of immigrants and ethnic minorities. As referred to earlier (see 1. Table) reducing the

proportion of early school leavers is currently a major policy goal

supported by one of the community benchmarks.

The promotion of information

technology in education has been a similar horizontal priority. The

importance of this was recognised at community level earlier than in most

members states and a number of specific programs have been launched or

supported by the European Commission.[11] Quality assurance and development is a

further policy priority that is relevant for all subsystems. The European

approach to quality has had a major impact on national approaches, especially

regarding such principles as the balance of internal and external evaluation,

the involvement of stakeholders in quality processes and the use of quality

management for strategic improvement.[12] Finally the

promotion of cooperation between education

and business has also been a permanent priority of community policies in

education.[13]

Recently the theme of education/business nexus has been

strongly connected with the issue of the contribution of education to innovation. Strengthening the innovation

capacity of the Union has been a central component of community policies having

a strong impact on education sectoral policy. Ministers declared 2009 the “European

Year of Creativity and Innovation” in order to “raise awareness of the importance of

creativity and innovation for personal, social and economic development; to

disseminate good practices; to stimulate education and research, and to promote

policy debate on related issues“[14] and now one of the “flagship” action programs of the Union in the

framework of the EU2020 strategy is about innovation.[15]

Lifelong learning as the general policy framework

Since the beginning of the last decade all education sector

reform policies of the European Union have been ranged under the umbrella of

lifelong learning (LLL). The notion of LLL covers all subsystems of education,

including informal and non-formal learning outside the formal education system

and it is now seen as a kind of new paradigm of thinking about the world of

education and education policies.

The content of community LLL policy

The idea to put lifelong learning into the very center of

community education policy goes back to the seventies when

the first major proposal for a community policy in education was formulated (Janne, 1973) but this became a central commitment of the

European Commission only following the creation of legal bases for community

actions in the education sector in the 1992 Maastrich

Treaty (European

Commission, 1993). The first detailed

and coherent policy for LLL was proposed by the European Commission at the very

beginning of the last decade following a one year long, active public debate in

the member countries (European Commission, 2001). It is important to stress that this has been

initiated as a “shared policy” of the employment and the education sectors.

Making LLL policy highly operationalised and explicitly formulated became

inevitable by the

launching of the policy coordination process in employment policy following the

Amsterdam Treaty in 2007.

As we saw, “making lifelong learning and mobility a

reality” is the first of the four priorities of the education sector strategy

adopted in 2009 for the current decade. Since its inception the LLL

policy of the community has been confirmed, extended and deepened by a number

of important decisions of the Council and the Parliament[16] but the main lines of

this policy are more or less the same as they were set at the beginning. The so

called “building blocks” of this policy (see box below) together have created a

new paradigm that seems gradually to gain ground in the member countries partly

due to the use of the community policy instruments (to be presented in more

details below) supporting implementation. Since every member state is supposed

to devise and implement a national LLL strategy, and both the strategy and its

implementation are regularly evaluated by the community, there is a high

probability that the European strategy has a significant influence on the

content of the national documents and its building blocks do appear in the

latter.

The key components of the LLL policy of the European Union[17]

ð “Valuing learning” (recognising competences acquired in informal and non formal learning; learning outcomes based qualifications reform)

ð “Information, guidance and counselling” (the development of lifelong guidance systems and European policy cooperation in this area)

ð “Investing time and money in learning” (promoting regulatory policies that support individual and company investment into learning)

ð “Bringing together learners and learning opportunities” (promoting flexibility in employment and education regulations so that they make it adult learning easier)

ð “Basic skills” (defining new standard frameworks for key competences and re-directing teaching to develop these competences)

ð “Innovative pedagogy” (enhancing innovation in education, especially in classroom level teaching/learning so that learning environments become more favourable for lifelong learning)

Since it has become the basic framework of community

education policy more than one decade ago the paradigm of lifelong learning has

gone through some evolution but, as mentioned, its basic pillars have remained

broadly the same. Lifelong learning has always been understood in a very broad

sense in the EU, encompassing all forms of learning from early childhood

education (which has recently become a major priority area) to the workplace

learning of adults. A key feature of this paradigm is to put the learner (the

demand side) into the centre of education and training policies instead of

providers (that is, the supply side), which has far-reaching implications for

all policy aspects including legal regulation, funding or pedagogy. Opening the

education sector towards the “outside world”, that is,

strengthening its connections with the word of work and giving business a

greater role has ever been a major priority in community education policy. This

orientation has sometimes been criticized by those who think the education

policy pursued by the EU is too “instrumental” or too much oriented by

“neo-liberal values”(e.g. Field, 1998, Borg–Mayo, 2007; Lee–Thayer–Madyun, 2008).

A central element: reforming national qualification

systems

From an EU perspective the most important component of national LLL strategies and reform policies is, as already referred to earlier, the development of national qualifications frameworks (NQF) in accordance with the common European meta-framework (EQF). According to a recent official EU report by October of 2012 29 member or candidate member countries were developing or have already designed a comprehensive NQF covering all types and levels of qualifications. NQFs have been “formally adopted” in 21 countries: four of them have „fully implemented” their NQFs and seven of them were “entering an early operational stage” (CEDEFOP, 2012).

A particularly interesting element of this

implementation process is the so called “referencing”

which aims at checking whether national categories match correctly the

corresponding European levels (Coles, 2011). This is the condition for national

awarding institutions to issue national diplomas or other qualifications

containing an indication of their “European level”. Since this is in the

interest of the citizens who have obtained these qualifications there is a

pressure on national governments to perform the referencing process even if

they are not legally bound to do so. And, since the European framework is based

on defining learning outcomes, national frameworks have also to follow the same

logic.

One of the most important outcomes of the progression of

LLL policies, including the implementation of EQF, is the blurring of

borderlines between the various sub-systems of education, on the one hand, and

between sectoral policies affecting the development of education, on the other.

It is now difficult to draw a sharp distinction between policy areas such as

education, employment, social care, regional development or innovation policy.

The LLL approach has created a kind of common policy space in which measures

taken in the various policy areas reinforce each other and create synergies.

The advancement of LLL policies in the member countries has now reached a stage that we could perhaps describe as a new policy generation often called skills policy. (European Commission, 2010b; OECD, 2012). Skills policies tend to put a strong stress on the demand side (as opposed to the supply side), they put more stress on workplace or work-based learning (as opposed to learning in schools), they see skills utilisation as important as skills production, and they shift the attention from matching demand towards creating skills equilibrium (OECD, 2012; Campbell, 2012). A new skills policy for the European Union was proposed by the European Commission in 2008 and this became the object of one of the 7 flagship action programs supporting the implementation of the EU2020 strategy.[18]

The

higher education modernisation agenda of the community

The lifelong learning paradigm has given a new direction to community policies

related with all subsystems of education. There is one sub-sector policy that

deserves being treated in more detail because of its key contribution to the

Lisbon agenda and the EU2020 strategy: this is higher education. The European

Commission has continuously supported efforts to make higher education part of

the broader lifelong learning system, although European academic circles have

been reacting rather ambiguously to these efforts:. We can observe both

extremely positive and very reluctant reactions. The former can be symbolized,

for example, by the emergence of professional networks supporting “University Lifelong Learning”,[19] or by the adoption of the “European

Universities’ Charter on Lifelong Learning” by the European University

Association in 2008 (EUA, 2008). The latter can be symbolized by the high

number of “critical” analyses of both the higher education policy of the

community and the Bologna process.[20]

The higher education modernisation agenda of

the Union interacts in an interesting way with the intergovernmental Bologna

process, the latter aiming at the creation of a European Higher Education Area.

This is a typical pattern of European education policy making which often

transfers issues of contention either to other sectors, where the policy

environment is friendlier or outside the Union into policy spaces with a more

favourable dynamics (Corbett, 2011). This is also one of the examples of

member country governments using the community to legitimate policies that are

difficult to get through within their domestic policy-making machinery. In fact

a large proportion of the academic community in the member countries seem to be

reluctant to accept the higher education modernisation agenda of the EU. As

formulated in a recent publication: “there

is (…) concern, particularly voiced in some European university systems, that

by increasing university dependence on non-state resources and deepening their

engagement with industry and commerce, universities will lose their freedom to

act in their traditional role as critics of society” (Shattock,

2008; 14).

In fact, there are leading

European academics who think that the EU is going too far in subordinating

higher education policy to the needs of economic growth, competitiveness and

employment and they are not happy with the proposal of the Commission to “involving employers and labour market

institutions in the design and delivery of programmes, supporting staff

exchanges and including practical experience in courses can help attune

curricula to current and emerging labour market needs and foster employability

and entrepreneurship.” (European Commission, 2011; 5).

Some observers describe the higher education

policy of the EU as efforts to reformulate the existing tacit contract between

higher education, the society and the state. This is a difficult process

supported half-heartedly by a large part of the European academic community

which has been often accusing the EU of being too “instrumental” in its

thinking about the goals of higher education. This was expressed recently in

the following way in the keynote speech of a leading European higher education

researcher at an EU conference during the Polish presidency: “European higher education systems will have

to find a fair balance in expected transformations so that the academic

profession is not deprived of its traditional voice in university management

and governance; so that the European professoriate still unmistakably belongs

to the middle classes; and so that universities are still substantially

different in their operations from the business sector, being somehow, although

not necessarily in a traditional manner, ‘unique’ or ‘specific’ organizations”( Kwiek,

2012; 9).

The higher education policy

of the European Union is strongly influenced by its innovation (or research and

technology) policy. The latter has ever been a key element of community

policies but it was given a new impetus within both the Lisbon agenda and – as

mentioned above – in the EU2020 strategy. A related study rightly stated a few

years ago that “higher education and research are interpreted as sub-systems of

a larger overall European innovation policy” (van Vught,

2009; 18). The innovation policy of the European Union is very strongly

connected with industrial policy. As one of the relevant

websites of the European Commission puts it: “Innovation policy is about

helping companies to perform better and contributing to wider social objectives

such as growth, jobs and sustainability”.[21] Most university leaders as well as decision

makers in higher education policy share the idea that universities should play

a stronger role in making European enterprises more competitive through

boosting innovation. This has been recently manifested by the creation of a

platform entitled “Empower European Universities” by “eminent thinkers and practitioners of

higher education” with the aim of putting more pressure on national governments

to shape national higher education policies so that they serve better the goals

of European competitiveness and innovation.[22] These “thinkers and practitioners”

– led by the Dutch ex-minister and former vice-president of the World Bank Jo

Ritzen, who is one of those politicians who made,

during many years, perhaps the most for advancing European cooperation in the education sector

– share the idea that universities can “save Europe from its current economic

problems” and “universities can contribute to recreating hope and optimism

through more innovation in the economy”.[23]

The implementation of community education policies

The responsibility for the

implementation of community policies is shared between the member states and

the European Commission. The common discourse describes the European Commission

as the “government” of the Union. It has, in fact, at its disposal a wide range

of policy implementation instruments, similarly to national governments,

excluding one: legislation.

Governance and policy instruments

Law making in the European

Union is the prerogative of the Council of ministers and the European Parliament

which adopt the policy proposals of the Commission and translate them into

legal actions. The Commission is not, however, without power and effective

competence. The “indirect” or “soft” competences of the Commission are

particularly important in the education sector where the law-making competence

of the Union is very limited: it is, according to the EU Treaty, supposed to supplement and support and not to replace the actions of national governments. The

European Union, unlike its member states, does not have direct responsibility

to provide educational services. Its main function is to promote development

and modernisation, and the instruments it uses are the product of a several

decade policy evolution. Today it commands sophisticated institutional mechanisms

that one can describe as consisting of the following key elements: (1)

structural and cohesion policy, (2) cross-sectoral instruments, (3) educational

programs, (4) policy coordination, (5) knowledge and information management.

Structural

and cohesion policy is probably the most

important as it is served by two major funds: the European Social Fund

and the European Regional Development Fund. The Commission uses them to

support structural adjustment in the member states and the reduction of development

disparities between them. The former is under the supervision of Directorate of

Employment and Social Affairs Directorate, the latter is managed by its

Directorate of Regional Development. Since the beginning of the last decade

supporting the modernisation of national education systems figures among the

goals of structural and cohesion policy and money from these funds can be used

for this purpose. Education sector development programs are planned as part of

the multi-annual national development programs of the member states, typically

as a component of multi-sectoral human resource development or regional

development programs. They have to be in accordance with the general

regulations of the structural funds which specify the eligibility criteria for

community co-funding. Only educational development programs supporting growth,

employability and social cohesion can get community support, in accordance with

the strategies mentioned in the first part on this article.

Cross-sectoral

instruments or policy instruments of other sectors than

education are particularly important in the European Union for influencing

developments in the education sector. The “travelling” of policies from one

sector to another has always been an important element of the implementation

strategy of the European Commission (Halász, 2003). Sectoral policies are

nowhere isolated from each other and this is particularly true in the Union.

Lifelong learning and skills development are key components of employment

policy. Education is seen a one of the most important instruments of community

policies aiming at fighting against poverty and exclusion. As we referred to in

the previous paragraph, human resource development is a major component of

structural and cohesion policies as well as regional development policies. The

policy of common market and competition covers all areas of cross-border flow

of products and services, including the products and services of what we call

the “learning industry” (e.g. educational publishing, the educational use of

information technology or private provision of educational services).

Transferring policy issues from one sector to another is very common in the

Union: there have been many examples when policy initiatives were launched in

the sector where member states were the most receptive for them.

Those within the education

sector tend to see the so called educational

programs as the most important sectoral policy instrument, although the

resources available here are much lower than those

spent directly or indirectly on educational development through the structural

or the employment/social policy (Moschonas,

1998).

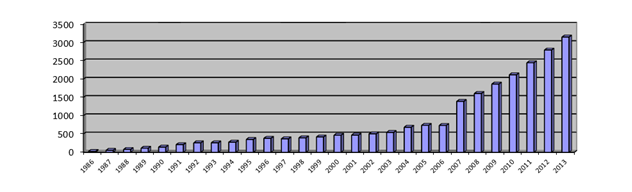

Education programs are, nevertheless, increasingly important as illustrated by

the continuous growth of their budget since the first of them was launched in

1986 (see 1.

Figure). Originally

there were separated programs for each subsystem of education – the names of

the original programs, connected to the four big subsystems (that is, Comenius

for schools, Erasmus for higher education, Leonardo for vocational training and

Grundtvig for adult education), are still in use – but today they are

integrated into the so called Lifelong Learning Program (LLP).[24] They fund a wide

range of actions such as student and teacher mobility, pedagogical innovations,

inter-institutional cooperation, various networking or policy development

projects. Funding from the educational programs is typically project-based:

proposals submitted by institutions or individuals are selected either by the

national LLP agencies of by a central agency in Brussels. Proposals have to be

in accordance with eligibility criteria defined by the Council decision[25] about the new generations

of programs and the selection is based typically on competitive open tenders.

1. Figure

The total budget of educational

programs 1986–2013

(million euro, current prices)

Source: European Commission (2006):

Source: European Commission (2006):

Policy-coordination

Since the decision on the

Lisbon strategy a new policy coordination mechanism has been developed

and applied also in the education sector. The so called Open Method of

Coordination (OMC) is an innovative method of governance in the European

Union tested first in the employment and social policy area following the

Amsterdam Treaty (1997). In 2000 the decision of the Lisbon European Council[26] opened the way

to apply it also in the education sector. Normally the OMC consists of four

components: (1) the setting of common policy goals, (2) the definition of

measurable indicators and benchmarks linked with these goals, (3) member states

translating the common goals into national action plans and reporting on

progress, and (4) community evaluation of national performance including the

formulation of country specific policy recommendations. In fact, OMC is applied

to education sector in two different, parallel channels. On the one hand, the education

sector has developed its own OMC mechanism in the “Education and Training 2010”

strategy framework and, later on, this was prolonged under the name of

“Education and Training 2020” strategy. [27] On the other

hand, education and training related elements appear also in the “big” growth

and employment strategy of the EU (the Lisbon strategy and, later, the Europe

2020 strategy), that is sectoral policy coordination takes place also in the

overall framework of coordination.

The OMC applied in the

education sector is a kind of “lightened” version: member countries are not

obliged to elaborate specific sectoral national action plans (although, as

mentioned, the education and training sector, together with others, appears in

the overarching national action plans for growth and employment). Countries

have been, however, obliged – since 2004 – to submit biannual education sector

progress reports to the Council and the Commission and the latter has performed

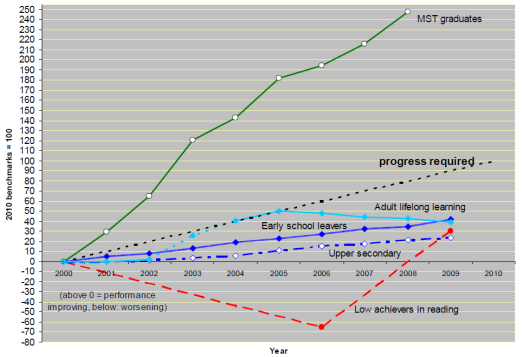

a regular evaluation of their policy achievements. This is

done for each individual country; and also for the community as a whole (see

the summarized results of the last such evaluation in 2. Figure). The figure

shows time series of values for five key targets: growth of studying

maths/science/technology, participation in adult lifelong learning, the

proportion of early school leavers, the proportion of those acquiring upper

secondary qualifications and the proportion of low achievers in reading. The

dotted line symbolises the target values, the five other lines the actual

achieved values of the five target areas.

2. Figure

The average value of

education sector benchmark indicators between 2000 and 2010 compared to planed

progression

Source: European Commission,

2011b

Policy coordination in every

sector, but particularly in education, is achieved partly through symbolic

instruments such as giving feedback and enhancing policy learning. The

community has devoted significant resources to develop activities that made it

possible for national authorities to take part in working groups and clusters

aiming at developing common frameworks and standards (such as the European key

competence framework mentioned earlier) and learning from the experiences of

those member states which have performed better than others in certain areas.[28] This leads us to

the fifth community policy instrument knowledge and information management.

In fact, the European Commission, having no direct regulatory power in

education uses knowledge and information spreading as one of the most important

tools to achieve its policy goals in this sector. The Commission is an advanced

knowledge broker in a perfect position as it sees developments at the same time

in 27 different systems. In the eyes of the Commission the 27 national systems

behave as living laboratories: trying out permanently various policy solutions.

Some of these solutions fail, but others survive and prove to be successful.

The Commission invests much into gathering, analysing and spreading information

about these processes. Given the fact that, contrary to national governments,

it does not have local executive branches, it is obliged to gather information

through various surveys and quasi-scientific analyses, which make it more

knowledgeable than most national governments having no similar knowledge

management facilities.[29]

The

future of education reform policies of the EU

The future of education reform policies of the

EU seem to depend on two main factors: the relationship between the community

and its members and the capacity of the community to influence the behaviour of

its members, on the one hand, and the relationship between policies in the

education sector and other sectors, on the other. During the past decades we

could witness two key trends. One was the continuously growing role of the EU

in education policy and its increasing capacity to influence educational developments

in its member states. The other was the permeability of borderlines between

education policies and other policy areas and the continuous possibility for

other sectors to influence the development of education. The key question is

whether these two trends will continue in the future.

If the answer to the second question is

affirmative we anticipate the continuation of the trend of education being seen

as a key factor in social and economic development, that is, in supporting

Europe to become more competitive in the emerging global knowledge economy

while preserving the values of equity, inclusion and sustainability. If the

first question is also answered positively, we can predict that the EU as a

community, instead of being an abstract entity above the concrete reality of

the member states, will remain a real common space for educational policy

development on the European continent.

As for the second question, the probability of

the affirmative answer is very high. Given the fact that the EU does not have

direct responsibility for the daily operation of systems of educational

provision, the vested interests of social actors whose fate depends on the

specific institutional arrangements of given sectors and of the different

subsystems of education do not play a dominant role in determining the content

of education policy. Thus, community education policy will remain future- and

reform-oriented, and it will not lose its openness to the variety of sectoral

agendas and approaches particularly in employment, social affairs, regional

development and innovation. The EU will probably continue to play a leading

role in fostering modernisation and educational reforms in Europe.

The first question – the potential impact of EU

on the member states – is less easy to answer. We see in several members states

the growth of “euro-scepticism”: it becomes more and more frequent that

political groups opposing the transfer of power from the nations to the

supranational entity gain power in national elections. There are strong actors

in each national education system that are not welcoming the modernisation

agendas – be they national or supranational – and therefore are not susceptible

to the current orientation of EU policies. They are, therefore, typically

opposed to EU interference into national affairs in the education sector even

if they have, in general pro-European attitudes.

There are perhaps three factors that

might increase the probability of the influence of the EU growing further. The

first is related with the current fiscal, monetary and economic crisis. The

crisis has been forcing member states, particularly those using the Euro as

their currency, to tighten monetary coordination and budget control. For

instance, the so called “European semester”, which is also described as “new

architecture for the new EU Economic governance”[30] mechanism, adopted by the member

states in September 2010 is now making possible the ex-ante coordination of

national budgetary and economic policies. The education sector cannot, naturally,

remain unaffected by this, even if the jurisdiction of the EU continues to be

very restricted in this policy area, since this process affects all budget

areas, without exception. The second factor is related with our second

question: the increasingly cross-sectoral nature of education policy. If the

opponents of the EU modernisation agenda get strength in national education

systems and make the dynamics of national education policy shift towards and

“anti-European” line, this will not prevent the penetration of education and

training related EU policies into the national systems through doors opened by

other sectors.

The third factor is connected with the internal

dynamic of the development of policy instruments within the EU. Some of them –

such as the instruments of structural policy and those embedded into the

education programs – are developed and redeployed in a cyclical way through

medium term re-planning. The rules of the use of the structural funds as well

as those of the education programs are re-formulated every seventh year based

on the experiences gained during implementation. As evaluations often criticise

the existence of parallelisms and the fragmented character of programs and the

lack of strategic coherence the re-formulating exercise typically results in

streamlining and in the reinforcement of strategic orientations. One can expect

this to happen also in the current revision period. Streamlining and

strengthening strategic lines always imply stronger community control and less

exposure to the specific fragmented interests of the member states. This would

mean, in the case of structural policy that member states will have to

subordinate their national development goals even more to common strategic

priorities, that is, they will have to devise, for example, education

development programs that will be even more linked with the overall

modernisation agenda of the Union. In the case of education programs

institutions and individuals in the member states will have to make even more

efforts, if they want to win community support, to demonstrate that their

proposals are in line with the EU priorities.

References

Borg, C. – Mayo, P. (2005). The EU Memorandum on Lifelong Learning. Old

wine in new bottles. Globalisation, Societies and

Education, 3(2). 203–225.

Campbell, Michael. (2012). Skills for Prosperity?

A Review of OECD and Partner Country Skill Strategies, Working Paper,

Paris, OECD

CEDEFOP

(2012).

Qualifications frameworks in Europe: an instrument for transparency and change.

Briefing Note (online: http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/publications/20509.aspx)

Coles, Mike (2011). Referencing National Qualifications Levels

to the EQF, European Qualifications Framework Series: Note 3, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union

Corbett, Anne (2011). Ping Pong: competing leadership for reform in EU

higher education 1998–2006, European

Journal of Education, 46(1), 36–53

EUA (2008). European Universities' Charter on Lifelong

Learning, European University Association. Brussels

European

Commission (1993).

Guidelines for community action in the

field of education and training, Commission Working Paper, COM(93) 183

final

European Commission (1996). Learning

in the Information Society. Action plan for a European education initiative

(1996-98), Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels

European Commission (2001). Making a European Area of Lifelong Learning a Reality. Communication from the Commission.

Brussels

European Commission (2006). The

history of European cooperation in education and training. Europe in the making

– an example, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European

Communities

European Commission (2007). Action

Plan on Adult learning: It is always a good time to learn, Communication

from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels,

27.9.2007. COM(2007) 558 final

European Commission (2008). Improving

competences for the 21st Century: An Agenda for European Cooperation on School,

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the

European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions,

Brussels, 3.7.2008. COM(2008) 425 final

European Commission (2010a) Europe

2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, Communication

from the Commission, COM(2010) 2020 final

European Commission

(2010b). New Skills for New Jobs: Action

Now, A report by the Expert Group on New Skills for New Jobs prepared for

the European Commission

European Commission

(2011a). Supporting growth and jobs – an

agenda for the modernisation of Europe's higher education systems,

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament,

the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of

the Regions {SEC(2011) 1063 final}

European Commission (2011b). Progress

towards the common European objectives in education and training (2010/2011).

Indicators and benchmarks. Commission Staff Working Document. Brussels

Field, John (1998): European Dimensions. Education, Training

and the European Union. Higher Education Policy

Series 39. London and Philadelphia: Jesica Kingsley Publishers

Gordon, Jean et al. (2009). Key

Competences in Europe: Opening Doors for Lifelong Learners Across the School

Curriculum and Teacher Education, Warsaw, CASE-Center

for Social and Economic Research

Halász Gábor (2003). European co-ordination of national education

policies from the perspective of the new member countries. In Becoming the best – Educational ambitions

for Europe (pp. 89-118), CIDREE-SLO, Enschede

Janne,

Henri (1973). For a Community education policy. Commission

of the European Communities.

Bulletin of the European Communities,

Supplement. 10/73

Kwiek, Marek

(2012). The growing complexity

of the academic enterprise in Europe: a panoramic view, European Journal of Higher Education

(online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2012.702477)

Lee, Moosung – Thayer, Tryggvi

– Madyun, Na’im (2008): The

evolution of the European Union’s lifelong learning policies: an institutional

learning perspective. Comparative Education, 44( 4). 445–463

Moschonas, Andreas (1998). Education and Training in the European Union,

Aldershot, Brookfield

OECD (2012). Better Skills, Better Jobs, Better Lives. A

Strategic Approach to Skills Policies.

Paris

Olsen, J.P. and Maassen, P. (2007). European

Debates on the Knowledge Institution: The Modernization of the University at

the European Level. In Maassen, P. and J.P. Olsen (eds). University

Dynamics and European Integration (pp. 3-22), Dordrecht, Springer

Ritzen, Jo (2012). Can the University Save Europe?, IZA Policy Paper, No. 44. Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for

the Study of Labor. Bonn

Shattock, Michael (2008).

Introduction. In Shattock, Michael (Ed.): European Universities for Entrepreneurship:

their Role in the Europe of Knowledge (pp. 11-21), EUEREK. Final report.

Sixth Framework Programme

Tomusk, Voldemar (Ed.)

(2007). Creating the European Area of Higher Education. Voices from the

Periphery. Springer. Dordrecht

van Vught, Frans (2009).

The EU Innovation Agenda: Challenges for European Higher Education and

Research, Higher Education Management and

Policy, 21(2). 13-34

The author

Dr. Gábor Halász is professor of education at the Faculty of Pedagogy and Psychology of the University Eötvös Loránd (ELTE) in Budapest where he is leading a Centre for Higher Educational Management. He teaches, among others, education policy, education and European integration, global trends in education and sociology of higher education. He is the former Director-General of the National Institute for Public Education in Budapest (now Institute for Educational Research and Development) where he is now scientific advisor. His major research fields are education policy and governance, comparative and international education, skills formation policies and theory of education systems. He has worked as an expert consultant for a number of international organizations, particularly the OECD, the European Commission, the World Bank, and the Council of Europe. Since 1996 he has been representing Hungary in the Governing Board of the Centre for Educational Research and Innovation of OECD (between 2004 and 2007 he was president, and between 2011 and 2012 acting president of this Board). For more information see Gábor Halász’ personal homepage: (http://halaszg.ofi.hu/English_index.html).