Gábor Halász

Coping with complexity and

instability in vocational training systems: the case of the United Kingdom[1]

Complexity and instability are challenges that all

vocational training systems have to face if they take the needs of the word of

work seriously and if they maintain strong and dynamic connections with it. Matching

the permanently evolving skills needs of thousands or millions of workplaces,

on the one hand, and the supply of skills produced by education and training

systems, on the other, has never been simple. As this has been recently

expressed explicitly by an expert study published by the European Commission in

the framework of the community policy on “New Skills for New Jobs” matching through planning based on formal

qualifications does not work. As the study stated: “instead, the emphasis

should be on building an agile system that responds to market signals and where

LMI [Labour Market Information system] informs consumers, providers and

funders, helping them to make more informed decisions,

rather than the state ‘planning’ provisions at a micro level” (European

Commission, 2010).

Although “employers often use qualifications to

describe what they seek in terms of required skills supply and they also use

applicant qualifications to filter the supply of skills so that they get what

they want” (Coles - Werquin, 2009) systems of qualifications and matching based on

them have never been able to reflect properly the complexity of the often

“capricious” or “chaotic” skills needs of workplaces. Countries are trying to

reduce this complexity, among others, through modernising their qualifications

systems and making them more transparent, with the aim of improving mediation between

the words of training and that of work. But reducing complexity has also a

price as “diplomas seem to less and less able to provide all the information

that is required for recruitment and promotion processes” (Planas et als, 2000). There seems to be a need for new mediation

mechanisms that allow higher level complexity which still can be kept under

social control. The vocational training policy of the United Kingdom offers an

interesting example for this. As the question of how to deal with increasing

complexity in vocational training systems has appeared as a crucial one in most

advanced national systems studying the UK model might be relevant for the

emerging European and global skills strategies.

Strengths,

challenges and

policy dilemmas in vocational training in the UK

The three explicit strategic goals of the skills policy of the United Kingdom as

they were defined a few years ago are (1) making education and training more demand-led, (2) making it more

responsive to the rapidly changing skills

needs of companies and (3) letting users,

particularly employers, have a decisive role in determining the content of

supply and the ways it is delivered (DIUS, 2007). All these goals lead to

increased complexity in the UK vocational training system which has already

been high due to various factors. One of these has been placing skills (or

competencies) into the focus of vocational training which has been a key

element of turning training policy

into a skills policy. The combination

of this, in addition, with a demand-oriented, market-type regulation approach

leads necessarily to particularly high level of complexity, instability and

uncertainty (Planas et als, 2000; Struyven - Steurs,

2004).

It is therefore not surprising that, when the

information for this analysis was collected during a field visit in February

2008, the simplification of the complicated skills development landscape was a

central theme in the UK. This was already a key item on the agenda of the first

(preliminary) meeting of the strategic board set up to coordinate the skills

policy, the UK Commission for Employment

and Skills (UKCES), which, following this, initiated a specific program to

cope with increasing complexity and instability (UKCES, 2008). The main reason

of this was that the high level of complexity in the system of skills

production was seen as a major obstacle to increase employer engagement, which has been a key priority of the skills

strategy of the Government.

The assumption behind the goal of

enhancing employer engagement in the process of skills creation and skills

utilisation has been that without it any of the three goals of the strategy

mentioned above could not be achieved. If employers – together with individuals

– are not actively expressing their demands, both individually and

collectively, the system cannot be turned into a demand-led one. If employers

do not actively address the education and training system with the constantly

changing needs of the world of work, this system cannot behave in a responsive

way. If they do not show pro-activity in their role of determining the content

of supply and the ways training is delivered the new channels of control and

influence will remain unused. One of the challenges the UK skills strategy has

been facing is that although it can work only if the level of activity and

engagement of employers is high its actual level, due to a number of historical,

social-economic and cultural reasons (Stanton – Bailey, 2004), has remained

relatively low.

One can accept, as a departure point

of this analysis, the assumption of relatively low level activity and

engagement of employers in the UK, and also the assumption that the increasing

complexity of the system of skills production or VET may have a negative impact

on this. There are however two things that have to be stressed. The first is

that strong employer activity and engagement can be expected only in an

environment that allows the complexity of the world of work and production to

penetrate into the education and training system. In other words high level

employer engagement in shaping and implementing training policies can emerge

only if these policies are strongly and directly reflecting the complexity of

the reality of the world of work. The second is that the attitudes of

employers, like other social actors, are not exempt of ambiguities: on the one

hand they want to reduce complexity, but, on the other, they continuously

contribute to its growth. This ambiguity can be observed, for example, in the

attitude of employers towards qualifications: on the one hand they wish a

simple, easily readable qualifications system, with a low number of entries;

but, on the other, they wish a system that reflects the specificities of the

skills combinations demanded by their particular company or sector.

On the field we were often told by those we met

and interviewed that the high level complexity of the system and the

bureaucratic constraints are among those factors that may impede better

employer engagement. One of the areas where strengths and challenges related

with employer engagement have been identified was, in fact, connected with

complexity, uncertainty and bureaucratic constraints. The strengths identified were

as follows:

·

Employers can find

various alternative routes for expressing their needs and asserting their

interest: they can use both individual and the collective channels. As

individuals (individual companies) they can negotiate specific skills packages

according to their business needs, they can buy tailor-made training programs,

they can create company specific qualifications and request their inclusion

into the national qualifications system. Collectively they can aggregate and

express their demands through sectoral bodies.

·

The existence of sectoral bodies allows

employers to express and assert their specific sectoral needs and interests and

prevents regionally or locally organised training providers to determine the

supply side. The parallel existence of regionally organised funding agencies

and the sectorally organised employer-related agencies creates a positive

dynamic and allows checks and balances.

·

The high variety of

routes and bodies allows key actors to have a role in a sophisticated bargain

processes and in the elaboration of agreements on the provision and utilisation

of skills. Agreements can be reached between actors representing the provider

of public funds (the state), the providers of training (schools, colleges,

universities) and the skill-users (companies, employers) etc.

·

Linking the demand side

with both individuals (learning accounts) and companies through specific

programs and institutions allows a good balance between the two key actors on

the demand side.

·

There are many interfaces

that allow a rich communication between the education/training system and the

world of work/jobs/companies.

·

The qualification system

has a high level flexibility that allows the cutting of qualifications into

smaller units (credits, modules) which allows employers and companies to

acquire the specific skills they need, and creates new qualifications according

to specific sectoral or company needs without challenging the integrity of the

whole of the qualifications system,

·

Companies can link the

offer of training with their specific business strategy or competitive strategy;

the system allows tailor made, personalised solutions that make it possible investing

into skills that may lead directly to the improvement of the productivity and

competitiveness of particular companies.

The other side of these strengths are challenges

that are also related with the level of complexity and uncertainty and also bureaucratic

constraints. The following could be identified:

·

There are too many

decision making, consultation, funding etc. bodies that make it difficult for

users to orientate themselves and to define clear-cut responsibilities.

·

Training providers might

be organisationally destabilised by the variety and volatility of skills

demands. It is difficult to harmonise the needs for institutional stability and

the needs for adapting rapidly to changing demands.

·

There are too many

channels for funding training and it is difficult to find the appropriate funds

for specific needs. It is difficult to control the ways public funding is used.

·

Institutions have to

comply with parallel quality standards which are not necessarily in harmony.

Competing quality criteria may destabilise institutions

·

There are too many

documents and frames that guide the definition of qualifications

·

There are too many

parallel surveys that provide often contradictory evidences for decision making

·

The complexity of

institutions and procedures is accompanied high level bureaucracy, heavy

administrative or regulatory burden

·

Changes are too rapid:

institutions, programs, “brand names” often disappear before users can get used

to them.

Related with these strengths and

challenges a number of policy issues, demanding reflection and action, could

also have been identified:

- How

to avoid employer engagement being seriously hindered by increased

complexity created by the demand-led system and by the opening of the

system of education and training to the rapidly changing specific skills

needs of companies?

- How

to reduce overregulation and bureaucratisation in a context where the

demand side gets control over public funds?

- How

to make the system more comprehensible for the users, especially

companies?

- How

to cope with increasing complexity? How could complexity be reduced

without jeopardizing the achievement of the strategic goals of making

education and training more demand-led, making it more responsive to the

rapidly changing skills needs of companies and letting users have a

decisive role?

- How

employer engagement can be generated, enhanced and maintained in a context

of high level complexity? How to create those mechanisms of governance and

regulation that are capable to cope with the increased complexity?

This article tries to understand the nature and

the sources of complexity and uncertainty in the vocational training system of

the UK, in the perspective of these strength, challenges and related policy

questions. It is in this perspective that it also tries to analyse the possible

impact of complexity and uncertainty on employer engagement. The article also formulates

some assumptions about the possibilities to, the needs for, and the possible

ways to reduce complexity.

The basic assumption of the article is that those

who manage systems can react to increased complexity in two ways: either they

can try to decrease it or they can try to create new mechanisms that allow

mastering it. In the case of the skills policy of the UK it seems clear that

reducing complexity beyond a certain level could be achieved only through

giving up some of the goals of the skills strategy (that is, through making

education and training less demand-led, making it less responsible to the needs

of the world of work and giving less role to the demand side, particularly

employers). As the commitment for these goals and the political support for

them seem to be particularly strong in the UK, this is probably not a real

option.

One can assume, therefore, that in this case

there is no other choice than to create and sustain new, innovative mechanisms

that allow those who are leading and managing the system to keep complexity

under their control. If this is done successfully, this may create an

environment that is favourable for the achievement of the original goals. These

mechanisms can make it possible to keep complexity at a relatively high level,

to live together with it, to reduce the risks that accompany it and to let all

those processes work that make it possible to reinforce further the demand-led

character of education and training system, to make it more responsive to the

rapidly changing needs of the world of work and to let employers have a

decisive role in determining supply. While discussing these issues with some of

the key leaders of the implementation of the UK skills strategy it was found

that they seem to be much aware of this challenge and that those mechanisms

that make it possible to keep the increased complexity under control are

already operational and they are being developed further.

As we shall see, one of the specificities of

the vocational training landscape in the UK is the very high number of actors

or partners who take part in the creation and the implementation of policies.

As an OECD review of adult learning has highlighted some years ago, “there are many different partners involved

in the definition of public policy and provision of adult learning and post

secondary education” in the UK (OECD, 2005). In connection with this it is

important to stress: reducing complexity for one actor (partner) appears often

as increasing it for another. For example, as we shall see below, reducing

complexity for employers can often be achieved at the price of increasing it

significantly for training providers.

Factors leading

to increased complexity

The VET model of the UK and its approach towards employer engagement

Contrary to many OECD member countries, and

similarly to some other Anglo-Saxon countries the United Kingdom does not have

a well established, clearly circumscribed vocational education and training

sector. Vocational education and training is provided by various providers,

some of them operating within the formal education system, and some of them

outside of it. This model is sometimes described as a “market model” (Ashton-Sung-Turbin,

2000) which is opposed to others, like the “corporatist model” of the German

speaking countries, the “developmental state model” of some East-Asian

countries or the “neo-market model” followed by some transitional countries

with emerging economies.

One of the characteristics of systems belonging

to the “market model” is, logically, that they focus less on the supply side (on provider institutions)

and more on the demand side

(companies demanding skills or consuming training services) than other systems.

This has been a characteristic of the UK model even before the current skills

strategy was designed. Since the demand side (with the huge variety of

companies which compete on various markets with various products) is always

more complex than the supply side (especially when supply is concentrated into

or monopolised by a well defined public sector) the model itself produces

higher level complexity than other models. This is reinforced by the fact that

in these models qualifications are also less regulated and people can do much

more jobs without being legally obliged to have a formal qualification. In

these systems there is more focus on the infinitely complex world of skills than on the more systematised and

regulated word of formal qualifications.

It is related with these characteristics of the system that the notions

“vocational training” or “vocational training policy” are much less frequently

used in the UK than in most other countries and the dominant public and private

discourse prefers using the terms of “skills” (e.g. “skills development”

“skills system”) or “skills policy”.

The current skills policy of the country can be

interpreted as an ambitious and dynamic attempt to improve radically skills

formation or skills production within the historically inherited VET model.

This policy which intends, among others, giving employers greater influence

upon training has led to the creation of a new institutional framework which

is, in fact, parallel to the already

existing one. While the governance and funding of training has been organised

basically on a territorial basis, the new institutional framework is organised

on a sectoral basis. Taking the model of various other countries with more

separated VET systems and stronger business representation into account

(Raddon-Sung, 2006; Sung-Raddon-Ashton, 2006) the UK decided to create new sectoral institutions,

the Sectoral Skills Councils (SSCs -

see more about this below in the section about governance and decision making).

On the one hand, this has created greater complexity by adding a new sectoral

structure to the already existing territorial one as it duplicated the

administrative and governance structures. On the other, however, it made the

VET landscape more comprehensible for the various the branches of industry and

for companies belonging to these branches.

A similar duplication, creating more complex

but, at the same time (at least for the business sector), more readable

structures is being carried out in the network of training institutions. There

are a relatively high number of types of institutions providing VET in the UK

but traditionally the institutional sector that has played the most important

role has been the network of Further Education Colleges (FEC). This is a

multifunctional institutional network providing education and training to the

post 19 age group (including adults) but often also for the 16-19 age group.

The VET functions in these colleges have not been well separated from other,

general education functions and VET in most of these colleges has not been

specialised, that is, it has not had a clear sectoral focus. For employers this

has made it difficult to identify those providers which have specific sectoral

strengths.

This arrangement has been by challenged various

programs aiming at creating new specialized training institutions with clearer

sectoral linkages and transforming

existing organisations into such institutions (see, for example, the programs

on Centres of Vocational Excellence and National Skills Academies). The White

Paper on FE colleges, published in 2006, formulated it clearly: “We will expect every FE provider to develop

one or more areas of specialist excellence, which will become central to the

mission and ethos of the institution and will drive improvement throughout it.”

(DfES, 2006). The emergence of a more specialized,

more sector-bound network of training institutions is adding a new element to

the already complicated VET landscape, increasing its complexity, but, at the

same times, it makes this network, or at least parts of it, more comprehensible

for industry, as the examples of a number of other countries prove it

(Otero-McCoshan, 2004).

Linking skills with company level business strategies

A second particular factor that increases

complexity significantly is the intention to establish a link between the

skills needs of companies and their overall business strategy. The skills

policy in the UK has been strongly influenced by labour market research

demonstrating that the simple increase of the supply of skills does not

necessarily lead to increased productivity and competitiveness. Productivity

and competitiveness of companies increase only if they modify their business

strategy and, through this, they create a need for new skills (see for example:

Keep-Mayhew-Payne, 2006; Futureskills Scotland, 2007; Keep, 2008).

This is, in fact the acceptance of the fact that supplying skills in itself is

not enough to boost productivity and competitiveness but there is also a need

to alter the complex “ecosystem” in which skills are utilized in a given

competitive environment and technological context.

This is one of the reasons why the Train to Gain program which offers,

among others, a given type of business consultancy service to the companies

(carried out by “skills brokers”) has become the "flagship" of the

UK's skills strategy. This aspect is much stronger in the Welsh Workforce and Business Development Program,

which is the correspondent of Train to Gain in Wales, and which offers overall

human resource development consultancy service to companies with a relatively

larger pool of HRD advisers. Both the English skills brokers and the Welsh HRD

advisers start their activity in the visited companies with preparing an

overall organisational needs analysis

that not only maps all the skills needs of the company but also links this to

its business plan. We heard, for example, from a skills broker that he started

his work in a firm operating in the construction industry by analysing,

together with the managers, the already concluded contracts and used this to

define what specific skills needs the company will have in the future. Skills

brokers may help human resource managers to establish a "skills

matrix" that describes the specific skills needs of each employee in the

light of the business strategy of the company.

Linking skills needs with the business plans or

competitive strategies of particular firms and integrating this into training

policy change the fundamental characteristics of this policy. It is not enough

to look any more at the overall qualifications needs of industry or specific

sectors but there emerges a need to take the singularities of every company

into account. The creation of advisory services that create bridges between the

infinite complexity of the skills needs of particular companies, on the one

hand, and the much more standardised and regulated word of training providers,

on the other, seems to be a logical answer to this situation. As a related

analysis stated: “adopting a skill

ecosystem approach challenges and confronts policy makers dealing with

education and training issues with a level of complexity to which they are not

normally accustomed” (Payne, 2007). This approach challenges the simple and

direct relationship between economic performance and skills and tries to cope

with the complexity of these linkages. By creating the services of skills

brokers and HRD advisers the governments of England and Wales have established

a new interface between the complexity of business strategies of particular

firms, on the one hand, and the much simpler skills supply system represented

by training providers, on the other.

This shift of focus towards the business

strategies of companies increases complexity in various ways. For example it

creates a problem of how to distinguish between those companies where investing

into skills will really improve competitiveness and productivity and those

where this would probably not have such an impact. This has an impact on how to

define the appropriate target groups, that is, companies where the public

support for skills development should go in order to obtain the most efficient

use. This would require, for example, making a distinction between companies

that are on the way to improve their market position or to conquest new global

markets and those who do not have such intentions, and to direct public support

for skills development to the former group (Keep, 2008). It is clear that

traditional training administrations are not prepared to cope with such a complex

task and this necessitates the active involvement of new actors, such as

various business support and employer organisations in the implementation of

the skills policy.

The UK policy change pattern

A third factor that increases remarkably the

complexity of the VET landscape in the UK and contributes to the situation

being perceived as very unstable is the particular paradigm of introducing

changes and innovations into the system. Looking at the rapidity of changes it

is not surprising that the word “revolution”

appears quite often in official government documents.[2] The OECD review on adult education has already

stressed that „there is constant change

and development in policies related to adult learning, there is a constant

change and creation of institutions and bodies devoted to different tasks

within the lifelong learning arena. In fact, many of the institutions involved

in adult learning have been created quite recently” (OECD, 2005). A well

known academic expert of the area described this instability brought by

constant and rapid changes in a critical lecture this way: “...for the health warning for those of you who have never been inside

the LSS[3] before. It is a vast

and complex world which is restructured so frequently that it has become a

full-time job just to read about the latest turns and twists of policy, never

mind respond to them. [This is a] fascinating, turbulent, insecure but

desperately important world” (Coffield, 2007).

Beyond the rapidity and the frequency of

changes there is a further characteristic of the policy change pattern that

increases complexity significantly: the culture of introducing new elements

into the system so that the existing ones are left intact until the new ones

prove their viability. This is very apparent, for example, in one of the reform

components of the skills strategy: the introduction of a new secondary school

leaving examination and certification, the so called Diploma. The Diploma is a

qualification that will orientate the education of the 14-19 age-groups. According

to the related implementation plan (DfES, 2005a) “there will be 14 sets of specialised Diplomas, at three levels up to

advanced level, covering the occupational sectors of the economy”. Although

the original reform proposal (the Thomlinson report) suggested that “the existing system of qualifications taken

by 14-19 year olds should be replaced” by the new diploma (DfES, 2005b),

the final decision was that the new Diplomas will be offered parallel to the

existing qualifications (see DIUS, 2008). This approach is different from what

is followed in Wales where the new diplomas will be integrated into the system

of the unified Welsh Baccalaureate Qualification (DCELLS, 2008).

The rapidity and the particularly radical

character of the changes are also increasing the complexity of both the process

of policy formation and that of implementation. As policies are

intervening into areas that have not earlier been touched by public policies

policy-makers are permanently faced with problems they are not familiar with.

They often have to create new terms (e.g. “skills broker”) and they need data

in areas that have never been covered by systematic statistical data collection

(e.g. the skills profiles and business strategy indicators of companies). The

meaning of terms, even in cases when meanings have implications for financing

or for the assessment of the success of policy interventions may often change.

For example concrete policy targets or financial benefits have been linked with

the term of “hard to reach employers”, but the meaning of this term has often

been changed, reflecting divergent views and shifting policy priorities. “Hard

to reach employers” have to be defined differently, if the stress is on

supporting all SMEs with an equity orientation than in the case when the

question is how to find those companies that may have a good chance to conquest

high technology global market niches but lack the ambition to do so (Keep,

2008).

It is often only during the implementation

process that policy-makers realise that certain solutions that seemed simple

and logical during the period of designing policies lead to unexpected

difficulties. For example when the mediation between companies and training

providers was made compulsory in the Train to Gain program, it happened that

some training providers and companies agreed without a broker then they

together tried to find a broker to sign their agreement in order to gain access

to funding (Keep, 2008). We think these errors and uncertainties are

unavoidable if policies are intervening into areas hitherto not touched by

public policies and when progress can be achieved only through policy

experimentation. Designing and implementing policies in such situations require

strong leadership, high level intelligence and high level problem-solving

capacity from policy-makers.

The emerging new regulatory environment of the

skills policy, as already stressed, allows the expression and assertion of

employer needs in different ways and at different levels. It seems to be

recognised that only the creation of various parallel ways and levels and their

simultaneous operation can assure the effective expression and assertion of the

high variety of skills needs of employers. This can be interpreted simply as

processes increasing complexity but, it can also be described as the creation

of mechanisms that improve the manageability of higher level complexity. In

this respect the UK follows more or less the same line as, for example,

Australia, where there seems to be an emerging consensus, both in the research

and the policy community on the need for new coordination and regulatory or

governance mechanisms (“coordinated flexibility”)

that allow higher level flexibility while preserving social control (Buchanan,

2006).

Domains

of increased complexity

Letting employers play a key role at various

levels and letting them enter various domains of VET policy makes it possible

for various employer interests and demands to be expressed and asserted

simultaneously. The domains where we can observe this happening, at various

depth and intensity, are the following:

- Governance and decision making

- Funding and funding mechanisms

- Standard-setting, quality

assurance, accreditation and evaluation.

- The qualifications system

- Information management and

process monitoring

Although the level of employer involvement and

influence is very different in these domains, all of them open particular

channels for employers to determine key processes in the VET area. Employer

engagement is being enhanced in all of these domains, and the way employers use

these different channels to influence VET processes continuously create higher

level of complexity. Complex systems of mechanisms have emerged within all

these five domains that allow complexity to grow further, but there are also

possibilities to reduce complexity without altering the basic characteristics

of the system. It is important to look at the key features in all of these

domains, and at the possible ways for and limits to complexity-reduction.

Governance and decision making

As the result of the developments of the last

few years the landscape of skills policy, skills delivery and skills

utilisation has become populated by an increasing number of players. The number

of involved actors and agencies with various roles and acting at various levels

is, as already stressed, very high and this makes it difficult to comprehend

the VET landscape even for those within the system (see 1. Figure). As a

report prepared by the National Audit Office in 2005 on the employers’

perspectives on improving skills for employment stressed: “some employers are confused by the range of information, bodies and

training promotional material available”. It is not surprising that this

report came to a conclusion, with two of its four points stressing this, that employers

demand significant simplification. As it stressed: employers wanted a “simple ways of getting advice on the best skills training for their staff”,

and they wanted to “influence skills training without getting weighed down by

bureaucracy” (National Audit Office, 2005). The high level of complexity was stressed as a

major challenge already in key strategy documents of the government (DfES,

2006; DIUS, 2007) and, later on, complaints on this appeared in many public

documents and publications. In 2009, for example, a report of the parliamentary

committee dealing with skills affairs stated this: “We heard pleas from

practitioners for simplification. Colourful phrases were used about how

training and skills provision looks to those who come into contact with it: ‘a

pig’s ear or a dog’s breakfast’, ‘a very complex duplicating mess’,

‘almost incomprehensible’, ‘astonishing complexity and perpetual change’. One

witness told us that ‘I do not think there is an employer in the land who

understands what the elements of the new system are, particularly pre-19’” (House of Commons, 2009a).

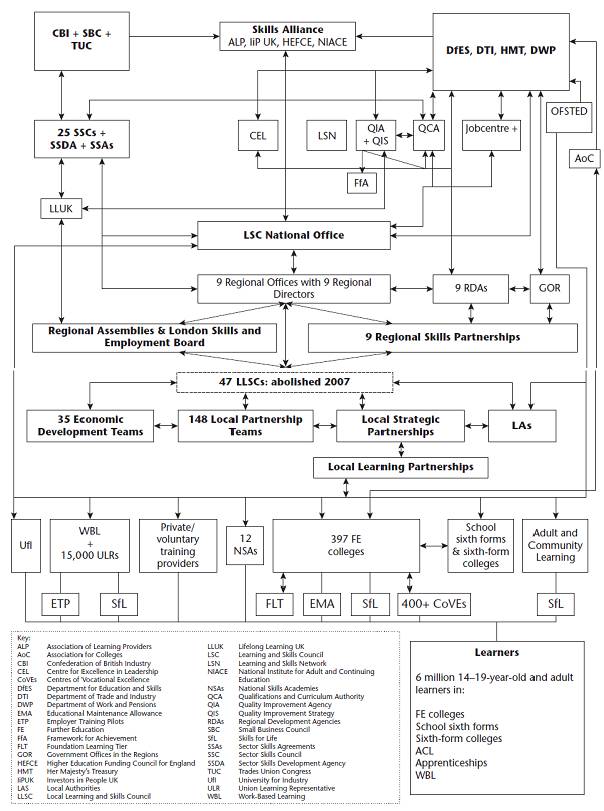

1. Figure

The

post-compulsory sector in England, 2006/2007

Source: Coffield et al.,

2008

The complexity of the system has been increased

significantly by the fact that, as already stressed, there are two parallel

channels to assert employer interests as both individual and collective needs

are recognised. Employers as owners or managers of individual companies can

express their specific skills needs through the Train to Gain program, the

flagship program of the English skills strategy or through the Workforce and

Business Development Program in Wales. These programs allow employers to define

and to formulate their firm-specific skills needs with the help of skills brokers (in England) or HRD advisers (in Wales) which are

services paid from public funds. Skills brokers and HRD advisers mediate

between particular employers and training providers and help employers to find

the specific training package they need. Larger employers may have access, with

the mediation of skills brokers or HRD advisers, to tailor-made training

programmes organised by training providers on their company base.

The mediation service, between employers as

“purchasers of skills” and training providers as “sellers”, provided by skills

brokers is one of those mechanisms that aim at coping with market complexity.

Skills brokers act as an interface between the word of work (companies) and the

word of education (training institutions). In this role they are confronted

directly with the complexities of these two different words and with, as it was

stressed by one of our interviewees, the huge cultural differences separating

these worlds. A study prepared by the relevant state agency (giving a positive

overall evaluation of the skills brokerage service) in 2007 stressed however

that “skills brokers work with

insufficient information to successfully match the strengths of particular training

providers to the needs of a particular employer or group of learners [...].

Many do not know enough about the skills needs of workers in particular sectors

or about specific training courses or qualifications which could meet these

needs. Qualifications and training courses are proposed based on very little

information about learners’ needs. Skills brokers give training providers too

little information on which to base meaningful training proposals that reflect

the needs of different groups of staff” (Adult Learning Inspectorate,

2007).

Parallel to the market-type mechanisms

employers also have the opportunity to express and assert their skills needs

collectively through the 25 Sector Skills

Councils (SSC). The creation of SSCs has duplicated the national network of

agencies responsible for the implementation of the skills policy. They operate

parallel with the network of those regional agencies, the regionally based Learning and Skills Councils (LSC),

which are responsible for steering and funding the institutional network that

has the strongest role in providing vocational training in the UK, that is, the

Further Education colleges. These two lines are complemented by a third one,

composed by agencies responsible for regional social and economic development (Regional Development Agencies - RDA).

The parallel regional and sectoral governance structures (the first for the

supply side and the second for the demand side) make the governance of the UK

VET system particularly complicated but, at the same time this allows a dynamic

interaction between the supply and the demand sides. SSCs have an increasing

role in all levels of VET policy, and they became key players at various

levels.

Although there might be overlaps between the

jurisdictions of these three lines of actions and related agencies each of them

have their well defined functions that justify their separated existence. This

creates a complex environment for policy formation and implementation and for

the daily operational running of the skills system, including policies aiming

at improving employer engagement. One of the ways to assure better coordination

and coherence between these subsystems is to give a key strategic leadership

role to a national board or agency that overlooks the totality of skills policy

and acts as the most important background for government decisions. This type

of role has been given to the UK Commission for Employment and Skills which has

a key role in driving and shaping the skills and employment system to meet the

needs of employers. While this Commission is connected to the sectoral line, it

also acts as the main advisory body of the government in the whole area of

skills policy.

Employers are complaining not only about the

complicatedness of the system of skills policy and skills delivery but also

about being weighed down by

bureaucracy. Bureaucratic procedures are strengthened first of all by the fact

that the use of public money by private companies makes strong public control

necessary. This is exacerbated by the high level “risk awareness” of those

designing and implementing programs in the relatively new field of skills

policies, where most of the mechanisms and institutions are new and the

procedures have not yet been stabilised. Our interviewees reported about the

fear from public scandals as the public and the media is vigilantly

scrutinising the use of public resources in the profit-oriented business

sector. This leads to over-insurance in the form of strict eligibility control,

high number of detailed standards and control of compliance to these standards,

and tough accounting procedures.

The scope

to reduce the complicatedness of the policy and delivery landscape seems to be

rather limited. In fact all the agencies and actors that emerged during the

past few years seem to have their functional place in the complex “skills

policy ecosystem”, none of them seems to be superfluous. One possibility to

help employers to find their way in this complicated word is to improve client

services and to make the operation of public bodies more client-friendly,

following the practice of “no wrong door”,

that is enabling employers to get the appropriate advice, or service at

whichever public organisation they approach. All public bodies have to accept,

as a departure point, that employers, particularly SMEs, want “a quick and obvious route to obtain good

advice and clear jargon-free information, require clear signposting because

they can be deterred by having many options” (National Audit Office, 2005).

As for easing bureaucratic burdens, a promising way could be what we saw in

Wales where there is a commitment to increase the discretion the employers in

using public resources if they meet certain standards.

Funding and funding mechanisms

Not only

governance and decision making but also funding becomes more complex in the

increasingly employer controlled and demand-led system. Some of the key factors

that contribute to growing complexity in the employer controlled and demand-led

VET system of the United Kingdom, particularly in England, are as follows:

(1)

resources are redeployed so that they come

under the control of various users,

(2)

services are increasingly tailored to specific

user needs,

(3)

public and private resources are combined,

(4)

employers use both individual market-type and

collective mechanisms to influence funding and

(5)

funding is increasingly used as an instrument of system-steering by public

authorities.

As the

growing complexity of funding can also become a major obstacle to the further

development of employer engagement the possibilities of making things simpler

and more transparent in this area is a major concern in the shaping and the

implementation of the skills policy of the United Kingdom. This requires a

serious analysis of the causes of high complexity and complicatedness and,

particularly, the careful distinction of those factors that are directly

related with the strategic goals (building a demand-led system with strong

employer influence) and cannot be changed without giving up the goals and those

that can be altered within the current strategic framework.

One of

the evident causes of high level complexity in funding is related with the key

dilemma of voluntarism and the

acceptance of sectoral differences.

As the government is reluctant, for various historical reasons (see for example

Ashton-Sung-Turbin,

2000; Coffield, 2002; Stanton Bailey, 2004; Gleeson-Keep, 2004) to introduce compulsory training

levies that would follow similar standards in every sector and as it allows the

different sectors to reach their own particular agreement and to proceed at

different paces, the complexity of the funding system is unavoidably growing.

Some sectors are much more willing to contribute to training than others; some

of them are already contributing while others do not. This prevents the

establishment of a clear and standard financing mechanism that other countries,

which do not follow the principle of voluntarism, can establish more easily.

The

complexity in funding is being dramatically increased by the current

redeployment of resources so that an increasing part of them comes under the

control of users (individuals and companies) instead of remaining under the

control of the providers. The creation and the use of individual “skills

accounts” and the English Train to Gain program are those mechanisms that allow

funding to be controlled by individual and corporate users. According to the

document presenting the implementation strategy of the government the resources

to be used in the employer controlled Train to Gain scheme will increase from £440 million

to £1.3 billion between 2007/08 and 2010/11 (DIUS, 2007). However, as monies do not go directly and

physically to the users but remain with the relevant accountable public

agencies, complicated mechanisms have to be operated that allow both users to

decide on what they spend the money on and the public authorities to control

whether spending meets the relevant eligibility criteria.

The

mechanism is further complicated by the fact that in an increasing number of

cases public and private financing are combined, that is some parts of a

“training-package” bought by an employer can be paid from the budget of the

company while other parts from the public purse. The public-private combination

appears also on the supply side as in many cases the “training-packages” are

offered by consortia of training providers which may consist of both public and

private institutions (one of them being the main contractor and the others

being subcontractors). Those “training-packages” that companies mount with the

help of the skills broker in the framework of the Train to Gain program are

increasingly tailor-made, based on the specific skills needs of particular

companies. The funding resources of such “training-packages” may also be

various, as in many cases the costs of such packages are covered from various

public and private, domestic and European, national and local, sector specific

and sector independent sources. Among the sources, monies coming from regional

or community development funds also occupy a significant place. One of the most

important tasks of the skills brokers in England is to find all the various

resources that can be used in accordance with the specific skills requirements

of companies and with the specific eligibility requirements of the providers of

resources. The complex landscape of resource providers is illustrated by 2. Figure.

2. Figure

A

simplified scheme of funding for employee training in England (2005)

Source: National Audit Office,

2005

A further

factor that increases the complexity of the VET funding system in the UK is the

fact that funding is used regularly as one of the most important policy

instruments for strategic steering in the decentralised, demand-led context.

This is one of those mechanisms that are used, as it was formulated by one of

the leading personalities of the skills policy implementation process, by

policy makers to “interact with the

system”. The various actors within the system (particularly employers,

learning individuals and training providers) are supposed to follow (with the

help of the providers of support services) the changes in the availability of

resources, in funding priorities or in eligibility criteria and to adapt their

behaviour to these changes. For example, in the period of our inquiry, in

accordance with the formal strategy of the government (DIUS, 2007) public funds in the Train to Gain program could be used – with some

exceptions – only for trainings leading to lower (NVQ2) level qualifications.

Using funding to alter the behaviour of users (encouraging individuals

and companies to invest into learning) increases significantly the complexity

of funding mechanisms, as well as the task of those who “play” on these mechanisms. A well identified challenge, often mentioned in relevant publications

(and also by several of our interviewees), is that that this way of using

funding as a policy tool unavoidable increases the probability of rewarding

private actors with public resources for actions that they would have done

anyway (deadweight). This makes it

necessary the permanent collection of good quality data that permit the

analysis of the behaviour of various actors almost in “real time” and also the

difficult persuasion of the public that up to a certain level this type of

“wastage” of public resources is justifiable. Since this makes funding very

vulnerable to public criticism, public authorities feel obliged to operate

excessive control through highly bureaucratic accounting and regulation.

Finally,

the complexity of funding is being increased also by its linkages with the

system of qualifications and the ongoing reform of this system (see more about

this in the section on qualifications below). If funding is linked with

qualifications, which is the case in the UK, similarly with other VET systems,

the complexity of the qualifications system unavoidably increases the

complexity of the funding system, as well. As qualifications are broken into

smaller units (credits, modules), it becomes possible to link funding with

these smaller units. This is, in fact, a deliberate goal of the current reform.

As some of our interviewees stressed, one of the ways to increase employer

engagement is to allow employers to “buy” only smaller units (credits, modules)

instead of whole qualifications. Employer organisations (the SSCs) when they

evaluate and approve qualifications, they evaluate and approve also smaller

units (credits or modules) within the qualifications. They can allocate various

credit-values to specific modules within qualifications and they can change

these values according to the labour market relevance they attribute to these

specific modules. The complexity created by this can be further increased if

the government follows the principle of giving more public support to trainings

that lead to full qualifications and less to those that lead only to partial

ones or offer only modules, as this could require quite complicated mechanisms

of credit calculation.

Since the

increasing complicatedness of funding mechanisms and the bureaucratic

mechanisms that accompany the development of them appear as one of the main

obstacles for enhancing employer engagement the goals of simplifying and

de-bureaucratising the mechanisms of funding became salient. This has to be

achieved, however, so that it does not impede the achievement of the main

strategic goals of the skills policy. One possible way to do this is to

strengthen the role of the leading institutions of training provider consortia

in coordinating and reporting, so that the employers do not have to care about

what kind of resources are used to finance the training package they receive.

Another possible way is to increase the discretion of at least certain

categories of users on how they use the resources they dispose of. This

possibility, which is, as already mentioned, envisaged in Wales, could be

offered for those who meet certain standards, for example they are the holders

of the Investors in People[4] award.

Standard-setting, quality assurance, accreditation and evaluation

The third domain where employers are encouraged

to and can in fact have a stronger influence on training and training provision

is standard-setting, quality assurance, accreditation and evaluation. This

allows employers to influence rather directly the operation of training

provider institutions. Through influencing the formulation of operational

standards and the operation of existing quality assurance, accreditation and

evaluation mechanisms or through initiating new ones they can partly determine

the way providers operate and they can influence the content of their training

products. A large part of this influence is exercised in the area of

qualifications (see next section for this) but this can focus also on the

operation and the organisation of training institutions. This is a good example

of how decreasing complexity for one actor may lead to higher complexity for

another. Having access to relevant and simple information about the quality of

providers (which are based on detailed standards and rigorous evaluation of

whether they comply with these standards) makes things simpler for employers

but may put extra burdens on providers.

The Government’s White Paper on Further

Education which was the basis of the new Further Education and Training Act

adopted by the Parliament in 2007 stressed not only in general the need to

strengthen quality assurance in training institutions but also that of linking

this better with the priorities of skills policy, including a better focus on

employer needs. The White Paper stressed that quality assurance should serve

the interest of the users (both employers and individual learners) and warned

against quality assurance leading to too much administrative burden and

bureaucracy.[5]

The

enhancement of employer engagement by training providers has been supported be

relevant state agency (Learning and Skills Development Agency - LSDA) for

several years. It published, for instance, guidelines for colleges and other

training providers on effective employer engagement as early as in 2003 and it

also conducted research on the impact of this on the internal management and

operation of colleges (Hughes, 2003; 2004). Setting standards for the

evaluation of how training providers (colleges) enhance employer engagement

made it necessary to define clearly what employer engagement means and also to

define performance indicators in this area. The LSDA research on how colleges

applied the employer engagement guidelines listed and measured 23 types of

employer engagement enhancing activities (such, for example, as setting a

strategic goal of increasing the number of employer clients, increasing

employer satisfaction or increase revenues coming directly from employers), and

provided data on the frequency of these activities within colleges (Hughes,

2004). This has, unavoidably, increased the complexity of the evaluation or

quality assurance processes and has led some growth of administrative burdens.

The

founding agency of further education colleges (LSC) has offered a standard

quality assessment framework based on three key areas: responsiveness,

effectiveness and finance. One of the performance indicator groups under the

area of responsiveness was responsiveness

to employers, which contained two specific performance indicators: employer

satisfaction and resources coming from employers (LSC, 2008). In addition to

this, a new further standard has been developed (with the active involvement of

employer organisations) which focuses exclusively on one single aspect: how

training providers satisfy employer client needs. As the relevant documents

formulate: “the New Standard is an

assessment framework and an assessment and accreditation process which has been

designed to recognise and celebrate the best organisations delivering training

and development solutions to employers” (LSC, 2007). By February 2008 there

were 27 training providers (most of them further education colleges) accredited

on the basis of the New Standard.[6] The creation of a specific standard for the

assessment of “employer friendliness” and a special accreditation process based

on these standards has certainly reduced complexity for the employer side as

companies searching for training can use the “New Standards” brand name as a

guarantee for good quality services. From the perspectives of colleges,

however, this new alternative form of accreditation has unavoidably created

ambiguity as it has, in a sense, duplicated quality assurance processes.

Concerns

about duplication and administrative burdens have been expressed, not

surprisingly, by the university sector which is also increasingly affected by

the challenge of supporting employer engagement. A position paper of the UK

association of universities (Universities UK) published in 2007 mentioned, for

example, several examples of “kite-marking” and endorsement schemes through

which SSCs are attesting the sectoral relevance and quality of various

vocationally oriented courses or certificates. According to this document

universities are faced with the following related challenges:

- “the development of endorsement schemes

could impose an additional regulatory burden on institutions, by

duplicating existing quality assurance arrangements;

- SSCs take a prescriptive approach to

accreditation, cutting across institutional autonomy, by defining learning

outcomes etc;

- in some cases such schemes cut across

accreditation already offered by professional bodies in a wide variety of

fields

- in some cases SSCs develop endorsement

schemes as a means of raising revenue, adding to the higher education

sector’s costs” (Universities UK, 2007)

As we

stressed the impact of introducing standards with the control of compliance

with them can both increase and decrease complexity. We identified one way of

using them to decrease complexity in Wales where, as mentioned, there is an

intention to simplify accounting and lessen administrative burdens on employers

through giving more discretion to employers in spending public money if they

meet certain standards. This is directly related with the intention of linking

skills development more strongly with the business strategy of companies. The

idea is that if companies have a coherent and advanced human development policy

embedded into their overall business strategy (which can be tested, for

example, through their meeting the Investors in People standards), and this is

publicly recognised, they can use public money for skills development with more

flexible eligibility criteria and without excessive reporting. This approach

can certainly reduce administrative burdens on the side of meeting eligibility

criteria and reporting, although at the price of paying the costs of complying

with standards and accepting external assessment.

The qualifications system

The qualifications system seems to be the most

important domain where employer engagement is enhanced and where increased

complexity is perhaps the most apparent. This is where many of the bridges

between the complex world of company level skills needs and the much simpler

word of training supply have to be built. The mechanisms developed here are

particularly complicated but most of these complicated mechanisms seem to be

necessary for the effective management of increased complexity.

There has emerged two parallel ways for

employers to influence qualifications. One, very recent, is the individual way, and the other is the collective one. Individually employers

have obtained the right to create their own qualifications and to make this

accepted by the qualification regulatory authority of the state (QCA), through

the so called “employer recognition scheme”. This is a radically new arrangement,

and the number of these types of "private qualifications" is still rather

low. In February 2008, a few weeks after the pilot scheme was launched, there

were, 3 such recognised company based qualifications: (1) the “Airline Trainer”

program of the air company Flybe, (2) the “Basic Shift Managers” program of McDonalds

and (3) the “Track Engineering” program of Network Rail.[7] A public authority, the Ministry of Defence has also received

the right to awarding recognised qualifications for three programs (“Heavy

Weapons”, “Carpentry and Joinery” and “Survival Equipment”[8]). In addition companies can acquire the right

to award publicly recognised qualifications through partnership with existing

awarding bodies (e.g. FE colleges or universities). In February 2008 there were

30 companies involved in joint awarding boards.[9]

The collective way of influencing

qualifications for employers is created through the SSCs. Within this channel

there are several complementary instruments, all of them having their own function. First SSCs are responsible for establishing a

strategy based on sectoral analysis about future sectoral skills needs and

skills gaps (Sector Qualifications

Strategies - SQS). It is on the basis of this that they define priorities

for certain qualifications or make it clear which qualifications are not needed

any more. Second, they negotiate this strategy with the most important

partners, those representing funding agencies and providers and agree with them

on the common realisation of their strategy. This negotiated agreement appears

in the so called Sector Skills Agreements

(SSAs). Third, they elaborate and regularly update a detailed qualitative description

of their specific skills needs in a document called National Occupations Standard (NOS). This document gives a precise

description of the skills (competencies, knowledge, attitudes etc) needed in

the typical occupations of the given sector. The NOS expresses the qualitative

skills needs of the sector and they constitute a basis for assessing existing

or new qualifications owned or proposed by the qualification awarding bodies

(e.g. training institutions). As mentioned above, SSCs will have the right to

approve or reject qualifications to be included into the National Qualifications Framework or to be selected for public

funding on the basis of how their content fits their NOS.

This collective system of managing

qualifications creates a kind of “double loop interface” between, the word of

skills needed at company level, on the one hand, and the word of training

supply, on the other, and it allows the control of higher level complexity. NOS

is one of the loops that is closer to the complex world of skills needed by

companies while the qualifications themselves constitute the other loop closer

to the world of education and training. In this system employers can assure

that they get the specific skills (and not qualifications) and education and

training providers (or qualification awarding bodies) can still be sure that

they can produce whole qualifications. This double loop interface between the

world of work and the world of training is operating under the strategic

control of employers who exercise this control in accordance with their

agreements with the key partners.

This already quite complicated system is being

made even more complex (and also more flexible) by the introduction of what is

sometimes called "unitisation" that is the credit or module system.

The National Qualifications Framework is being transformed, in England, into a

Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF), which will break down qualifications

into smaller pieces of learning units, which will allow people to accumulate

credits as they learn over time. One of the aims of this change is to give

qualifications simpler titles, “to avoid

confusion and overlapping names”.[10] Transforming the National

Qualifications Framework into a Qualifications and Credit Framework allows the

reduction of complexity at the level of the “brand names” (qualifications) at

the price of creating a second level, that of credits, which allows the control

of higher level complexity.[11] A credit and qualifications framework has

already been developed in Wales and Scotland.

Information management and process monitoring

As the UK is transforming its education and

training system towards a more demand-led and more employer-controlled system

and experiments with radically new solutions the needs for feedback information

about the impact of these changes is increasing exponentially. The growing role

of various actors acting as clients or pressure groups (companies, individuals,

employer organisations, new agencies etc.) which act autonomously and interact

with each other makes the evolution of the system less calculable and increases

uncertainties. The steering of this type of system demands much more fresh

information about various processes than the steering of a system where

processes are controlled by suppliers.

It is not surprising that while the number of

ad hoc and regular surveys that monitor changes in various domains (e.g.

employees, employers, programs, institutions etc.) is particularly high, the

need for further information seems to be never satisfied. One can see, on the

one hand, the extreme richness of evidences produced by various research and

monitoring programs, and, on the other hand, the ever increasing needs for

further evidences. It is quite probable that the need for new evidences will

increase further in the future. For example, as skills policy is increasingly

linked with the specific needs of particular sectors, there appears more and

more need for sector specific information. A further growth in information

needs may appear with the process of linking skills development and utilisation

with the specific business strategies of companies. If, for example, companies

with different business strategies express different skills needs, and these

needs are to be satisfied in a differentiated way some information on company

specific business strategies will be needed. This is well illustrated by the

discussion on how to define the group of “hard to reach” employers. If this

group may be defined (more in Wales than in England) as “firms that might be most likely to grow in size or where the

organisation showed an interest in trying to move its product market strategy

upwards, towards higher quality goods and services” (Keep, 2008), the type

of information needed to identify who belongs to the group and who does not

becomes much more complex than when this is defined according, for example, to

training practices or resources spent on training.

Policy

actions taken and related dilemmas

As has been stressed from the beginning of this

article, complexity, uncertainty and instability are naturally increasing in

any VET system that tries to be open to meet the rapidly changing skills demands

of companies competing in constantly changing markets. The challenge that he

VET system of the UK has been facing, under the social and political pressures

to reduce complexity, is how to achieve this without reducing responsiveness

and flexibility. In 2008, on the request of the government, as already referred

to, UKCES prepared a detailed analysis on the sources of high level complexity and

instability and proposed some specific policy measures for coping with it (UKCES,

2008). The report made it clear that there were many, very different and often

contradictory motives behind the complaints of employers about complexity and it

also made it clear that the possibilities of simplifying were limited. Similarly,

the government, when responding to the requests of the parliamentary committee

responsible for skills affairs, made it clear that reducing the complexity and

the instability of the VET landscape was not only difficult but it was not

always desirable. “We recognise the Committee’s call for a period of relative

stability” – said the Government in its answer. „But we need to balance the

benefits such stability would bring – in terms of employers getting involved in

skills and training their staff – with the reality of a rapidly changing

world”, making reference to the radical changes in the environment following

the economic crisis (House of Commons, 2009b).

The response of the Government and UKCES to the

request of reducing complexity and uncertainty was a sophisticated mixture of

action and non-action. A decision was taken not

to introduce new “disconnected activities”, not to request further reporting, not to establish new “brand names” for programs and not to create new agencies “beyond those

already announced” and to allow employers to do what they were doing in one

contractual framework instead of several. None of these decisions was removing

any of the key elements of the operating system. Beyond this, the launching a

number of positive actions has also been decided. On the top of the list of

these actions figured the creation of a new computerised information system,

with an attractive public internet portal, that allowed employers to have

access, through one single entry, to all skills-related services. This system,

called TalentMap[12], supported by several business

associations and government agencies and operated by UKCES has opened entries

for employers into five key skills-related areas: (1) staff development, (2)

recruitment of new staff with relevant skills, (3) improving business

performance through skills based innovations, (4) cooperating with schools and

other training providers and (5) participating in collective activities to

shape the skills system (e.g. influencing the definition of occupational

standards through the Sector Skills Councils). The title of the report assessing

the measures taken, published in 2009, was “hiding

the wiring”, making it clear that what happened was less policy-reshaping and

more improving communication and making things more understandable (UKCES,

2009).

Making things more manageable without altering

them substantially was in accordance with the original program of UKCES for

simplification. However, this program proposed also a second phase of

simplifying which was to be launched following a longer consultation process.

The original intention in this second phase was to also allow „rewiring the circuit board” (UKCES,

2008), that is introducing more substantial changes. One of these might be the gradual

elimination of a key source of complexity: the historical separation between vocational

and higher education. The idea of merging the public funding agencies of these

two sectors, for example, has been proposed several times by some key actors,

and this was also discussed in the already quoted report of the Parliamentary

Committee dealing with skills affairs. As the report formulated „there is a

significant discrepancy between the funding available to HE and that available

to FE. Some have argued that this difference has to be addressed if the two

sectors are to work together more effectively.” The Parliamentary Committee

took, however, a very cautious stand on this particularly contentious issue:

“We conclude that this is an idea whose hour has not yet come but one which

should not be dismissed as without merit” (House of Commons, 2009a)

Conclusions

The report of OECD on the VET policy in England

and Wales rightly stressed that VET policies in the UK are “more complex than

in most other OECD countries” and the landscape is not only complex but „also

volatile” (OECD, 2009). It is logical that the report, in accordance with the

need expressed by almost all players of the VET scene in the UK, recommended

that „institutions of the VET system should be simplified and stabilised”. “Hiding

the wiring”, stressed the report, „is useful to an extent but it is limited”. It

supported UKCES in its intention to prepare, following the closure public

consultations, a further report which might envisage „more radical changes”.

The key message of this article is that (1)

increasing complexity and high level instability are among those factors that

may seriously impede employer engagement but (2) complexity and instability are

caused mainly by the rapid changes and they are strongly linked with the basic

strategic goals of the skills policy of the UK (that is with linking skills

development with the rapidly changing skills needs of competitive industrial

sectors). This means that the necessary efforts to reduce complexity and

increase stability have to be made in a cautions way, so that they do not make

harm to the achievement of the basic strategic goals. It has also been stressed,

that in a changing and turbulent environment reducing complexity and increasing

stability from the perspective of one partner can be achieved often only at the

price of creating higher level complexity and instability for another.

There are, however, many possibilities for

reducing complexity and increasing stability even in the current changing and

turbulent environment through, mainly, increasing communication, making the

complicated new procedures and institutional arrangements even more

transparent, and particularly through trust-building that allows further

discretion, more flexibility and less bureaucracy. But, in many cases the

solution will probably remain “hiding the

wires”. That is showing to employers and other actors only those elements

of the complicated arrangements that are indispensable for their particular

action and keep all the others “under the cover”, uncovering them only when

there is a particular need for this (when, for example something does not work

and some procedures or institutional arrangements have to be fixed).

What we see when observing the VET policy

landscape of the United Kingdom seems to reflect two broader trends. One is the

emergence of advanced systems of lifelong learning with blurring boundaries between

the world of formal education and that of job-related learning and with new

mediation mechanisms. The other is the unstoppable trend of growing social

complexity that characterise all social systems, and which makes it necessary

for public policies to invent innovative new forms of steering and regulating.

The case of the VET (or skills) policy of the UK is a good example of how public

policy can learn now ways of coping with high level complexity and uncertainty.

Although all important players of the VET policy scene of the UK are expressing

worries and complaints because of the high level of complexity and uncertainty and

they are urging measures to reduce it, what is really interesting in this scene

is not these worries and complaints, neither the immediate policy reactions to

them, but the emergence of new innovative

mechanisms which, as shown particularly in the chapter on “domains of

complexity” are creating an emerging new potential to cope with complexity and

uncertainty. This is close to what Robert Geyer, a researcher on politics,

complexity and policy called a few years ago in one of his articles about

„third way” politics the „non-linear

paradigm” (Geyer, 2003). This type of public policy, that he positioned

between what he called the linear

(order) and the alinear (disorder) paradigms,

might offer significant competitive advantage to those countries which are able

to maintain relatively high level of complexity in specific policy areas

without losing control.

References

Adult Learning

Inspectorate (2007): The Impact of the Brokerage Service on Learners – A Review

by the Adult Learning Inspectorate, Coventry. Ofsted

Ashton, David - Sung,

Johnny - Turbin, Jill (2000): Towards a Framework for the Comparative Analysis

of National Systems of Skill Formation. International Journal

of Training and Development, Vol. 4. No. 1. pp.

8-25. Mar 2000

Buchanan, John (2006)